In 1994, the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Agriculture set the course for the liberalization and equitable organization of the global system of agricultural trade. The issue of food security was simply “noted” as a “non-trade concern”. Despite this legally peripheral status, food security seems to have taken on a politically central role in the ongoing agriculture negotiations.

In fact, it is the only agriculture topic to have been the subject of new commitments by the Organization’s members during the 12th Ministerial Conference (MC12) held in 2022, mainly to prohibit export restrictions likely to hamper the work of the World Food Programme. At a time when preparations are underway for the 13th Ministerial Conference (MC13) in early 2024, the Director-General has invited members to view the agriculture negotiations through the “lens of food security”.

How can the heightened stakes in this area be explained?

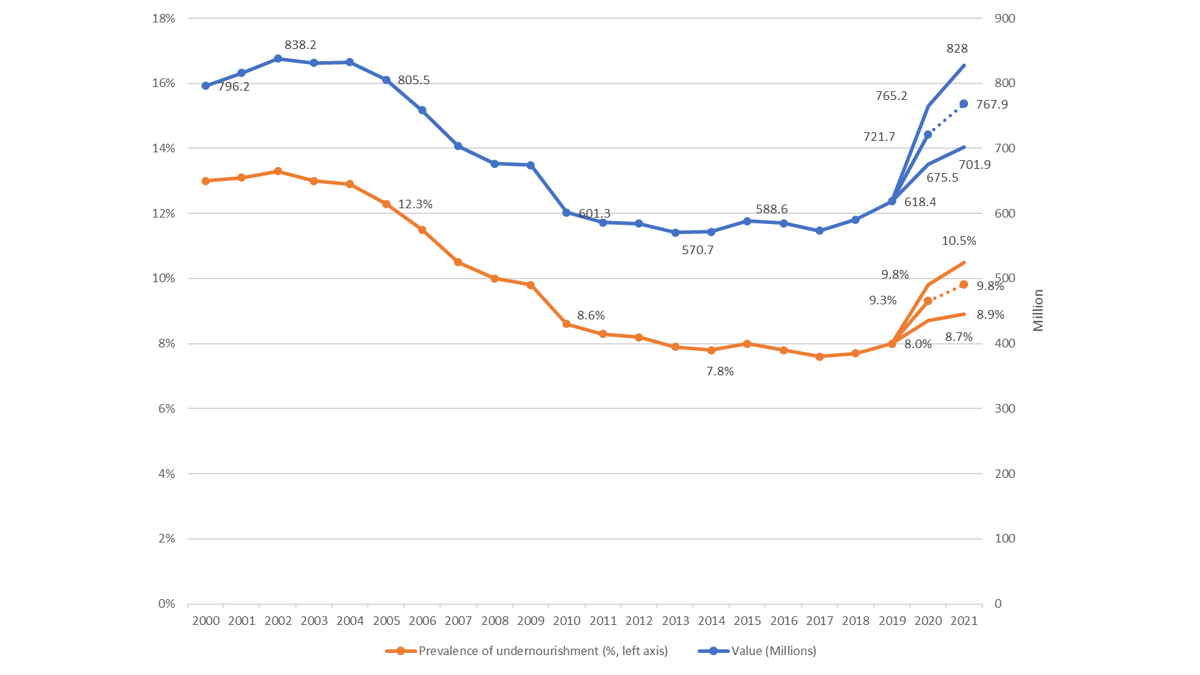

The immediate causes can be found in the recent upheavals in global agricultural trade. Climate disasters, the COVID-19 pandemic, war and successive economic shocks have undermined confidence in the security of global supply chains and have revived the notion of food “sovereignty” in several countries. Not without some reasons. These events have unravelled a decade of progress in combating malnutrition and have pushed 10 per cent of the world’s population into a situation of food insecurity, with 800 million men, women and children going hungry, 345 million people suffering from severe malnutrition and 45 million persons living with the threat of famine.

Number and prevalence of persons going hungry in the world in 2000-2021

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Food Programme (WFP) and World Health Organization (WHO) (2022), The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022: Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable, Rome: FAO.

Note: Estimates for 2021 are shown by dotted lines and are based on Food Insecurity Experience Scale data from 2014 to 2019. Shaded areas show the lower and upper bounds of the estimated range.

These external causes have been exacerbated at the WTO through the lack of progress in the agriculture negotiations, in particular as regards to agricultural subsidies emanating from the Uruguay Round or the specific handling of the cotton issue, so crucial for the so-called C4 countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad and Mali). However, the gradual reduction of trade-distorting support (amber box, calculated as Aggregate Measurement of Support) remains the shared objective of WTO members, many of whom are developing countries who wish to benefit from market interventions, particularly through their purchases for their public stockholding programmes for food security purposes at prices set by the government.

At the request of India and a group of developing countries, the issue made its way onto the agenda of the WTO Ministerial Conference in Bali in 2013. A temporary solution in the form of a peace clause protecting these public stockholding programmes when certain conditions were met was agreed until a lasting solution was found. But until now, the negotiations have failed to devise a permanent solution.

The combination of these factors has reopened a long-standing and deep discussion about the nexus between trade liberalization and food security, keeping in mind that international trade and domestic production are necessary to guarantee food security, as the ministers reaffirmed in Geneva at MC12 in 2022. The question is whether the focus should be placed on supporting domestic production or on opening up and diversifying trade. Whether it be subsidies or market access, the objective of the agriculture negotiations is to find the right balance between these two opposing views. From the Buenos Aires Conference in 2017 to the Geneva Conference in 2022, this equilibrium has still not been found.

What can the WTO do in the coming months?

First, it should continue to address the current food crisis. And the role of agricultural trade is crucial in that respect. This is because certain regions are structurally food-exporting ones (e.g. South America exports on average 60 per cent of its production) while others are structurally food-importing regions (e.g. North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa and several South Asian countries import on average 30 per cent or more of their food) and because Ukraine and Russia, who are currently at war, play a systemic role in this trade, with Ukraine alone accounting for over 10 per cent of global wheat exports, 15 per cent of global corn exports and 50 per cent of global sunflower exports.

The WTO’s role is to ensure the transparency and openness of agricultural markets when countries are tempted to keep their domestic production for themselves. Export restrictions are allowed in times of crisis under WTO agreements. But if all countries were to invoke them at the same time, trade would come to a halt and the crisis would worsen for each country. There is thus a collective interest in cooperating.

The WTO Secretariat monitors trade measures taken by members and this transparency helps to counter speculation about price hikes. WTO members have committed to exercising restraint with respect to restrictive trade measures to keep markets open as much as possible during times of crisis. These commitments are generally honoured. In fact, although the number of export restrictions rose rapidly at the start of the war between Russia and Ukraine, it then decreased and has stabilized to around 60. This is still obviously too high but at least has not led to any panic. The situation has generally remained under control. In parallel, members have adopted almost as many trade-liberalization measures on their food imports, thereby helping to keep markets running smoothly.

MC12 also saw the launch of a work programme on food security for least-developed countries (LDCs) and net food-importing countries.

The Organization has played its role in all forums tackling the crisis alongside the World Bank, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Food Programme and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), with close coordination at the level of agency heads. It was also part of the task force on the global food security crisis chaired by the UN Secretary-General, which facilitated with the assistance of Türkiye the conclusion of a key agreement with Russia and Ukraine to facilitate the export of grain and other foodstuffs from Ukrainian ports (the Black Sea Grain Initiative) as well as a Memorandum of Understanding on exports of Russian food products and fertilisers.

The trade development of the cotton sector continues to mobilize specific efforts in support of the C4. The WTO and FAO have presented joint recommendations to the G20 leaders to avert the risk of a fertiliser shortage. The WTO, the World Bank and FAO will report together to the G20 on food security at the forthcoming spring meetings of the World Bank Group and the IMF.

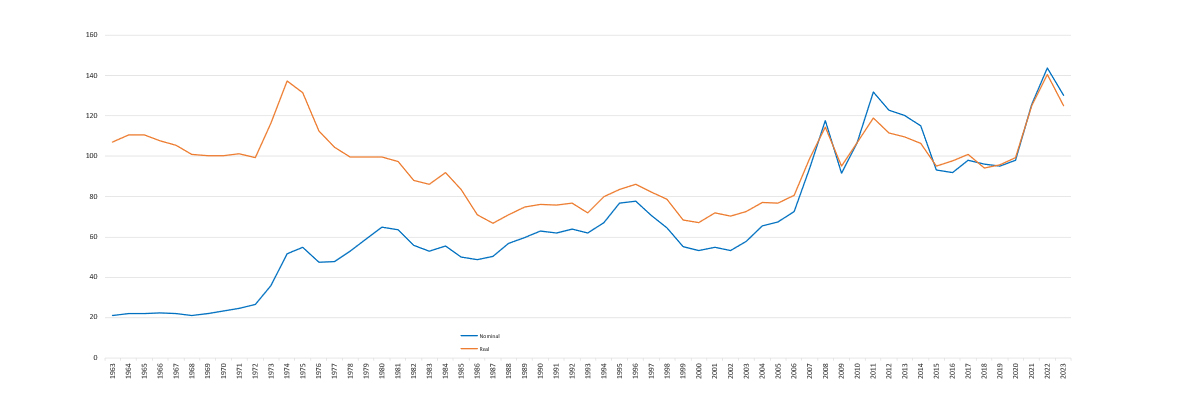

During this first phase of tackling the crisis, international cooperation and the resilience of international markets bore fruit. The FAO global food price index has dropped by 20 per cent since the peak recorded in March 2022.

FAO Food Price Index: 1963–2023

Source: FAO

How did the WTO contribute to this trend? It is difficult to say in the absence of a counterfactual scenario. But simulations conducted at the WTO Secretariat indicate that if there had been a proliferation of export-restriction measures, wheat prices might have increased by over 85 per cent in certain low-income regions (although the real increase was limited to 17 per cent). Despite that, world prices remain high and food price inflation is still too steep in many countries. The cooperation agreed at MC12 must be pursued. The next WTO ministerial conference will provide an opportunity to take stock and agree on new guidelines.

Looking beyond the current crisis, there is an urgent need to resume the negotiations on agriculture that have been stalled for several years on the usual issues (domestic support, public stockholding, market access, etc.) in order to promote deep reforms that will bolster the global system of agricultural trade and contribute to food security.

However, after several failures, many are openly sceptical about the prospects of these negotiations.

The WTO did, however, manage in 2015 to do away with agricultural export subsidies. That was a difficult but significant breakthrough for food security. I remember my years starting out as a trade negotiator, when frozen chickens exported by developed countries were flooding the markets in Africa at lower prices than the prices of domestic chicken!

Going forward, we must tackle distortions created by domestic subsidies, tariff and non-tariff barriers. Everything seems to indicate that it will not be possible to achieve this without taking a fresh view of the old “non-trade concern” of food security, which has further been exacerbated by new climate change challenges. That must include a solution to the question of public stockholding programmes for food security.

The Chairperson of the committee on agriculture negotiations, Ambassador Acarsoy of Türkiye, has decided to organize a series of thematic meetings. Engaging in technical and dispassionate discussions based on data and economic analysis from the WTO’s partners specializing in the field (FAO, the International Food Policy Research Institute, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the International Grains Council and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) seems a necessary first step for enabling a new mindset and starting on a constructive path towards the Organization’s 13th Ministerial Conference. This is what is at stake as Agriculture Week opens, with this edition focusing on food security.

Reach us to explore global export and import deals