Globalization at an inflection point?

Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen,

I’m really delighted to be here — thank you to Joe Gruber and the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City for the invitation.

The past three years have reminded us how much trade, on both the supply and demand sides, matters for macroeconomic stability. I’m convinced it’s important for central bankers and the trade community to work together. That’s why I left the G20 trade ministers’ meeting in India at the halfway point and flew straight here to join you. Jaipur to Jackson Hole was a new itinerary for me.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine exposed vulnerabilities in global supply chains, with disruptions and delays leading to product shortages and price spikes.

Sustained inflation has made a comeback across the rich world. And even as the picture improves within many advanced economies, spurring hopes of soft landings, monetary tightening has exacerbated debt distress and financial instability for dozens of developing economies.

Some policymakers have looked at these shocks, alongside rising geopolitical tensions, and concluded that globalization needs to be rolled back.

Over the next fifteen minutes or so, I will make the case that we should not wish globalization away. But I will argue that we can — indeed we must — improve it, and that doing so offers opportunities to advance growth, resilience, sustainability, and price stability.

I will make three main points.

- First, predictable trade is a source of disinflationary pressure, reduced macro volatility, and increased economic resilience. It has also been a major contributor to global growth and poverty reduction. Economic fragmentation would be painful.

- Second, falling trade costs for goods and especially for services mean that globalization can still be an engine for increased growth, efficiency, and economic opportunities, while also contributing to price moderation.

- Third, supply chains are already shifting in response to changing risks, costs, and technologies. These shifts create opportunities to bring in more countries into globalized production networks. This process, what we at the WTO are calling “re-globalization”, offers potential to boost productivity, growth, development, and long-term price stability.

Seizing these opportunities requires open and predictable international markets, anchored in a strong and effective rules-based multilateral trading system.

Our credibility at the WTO — that is, the extent to which people believe that governments will maintain market conditions broadly in line with multilateral rules and commitments — will help central banks with their credibility. The converse holds as well: a less predictable world for trade will make life more complicated for central bankers.

So let’s start by looking back at how trade has performed.

By expanding the international division of labour, international trade has fostered the productivity improvements that come with increased specialization, scale, and competition. For developing economies in particular, access to external demand has enabled rapid export-led growth.

Predictably open international markets, anchored in the GATT/WTO system, were critical in making trade an engine for global prosperity: market actors could scale up investment and orders, and be reasonably confident that they would not be unexpectedly cut off from export markets or imports.

Since the beginning of the 1990s, when the Uruguay Round of multilateral liberalization was complemented by market-oriented reforms in China, Eastern Europe, India, and other emerging markets, international trade has grown seven-fold in value terms, and quadrupled in volume.

Open markets combined with better communications to allow manufacturing production and processing to be unbundled into multi-country supply chains. This lowered the bar for entry into global markets — and for accessing the knowhow and productivity gains that come with participation in those production networks.

The boom in trade was a pivotal factor in the sharp reduction in extreme poverty, from nearly 38% of the global population in 1990 to just over 8% in 2019, according to World Bank data.

With regard to prices, there is considerable evidence that trade liberalization and the rise of modern supply chains were disinflationary

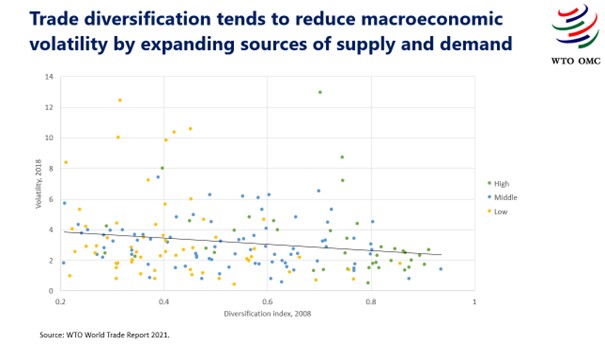

Research shows that openness to international trade lowers macro-volatility more than specialization increases it By allowing countries to diversify sources of both demand and supply, trade integration reduces exposure to domestic shocks, whether they are caused by economic downturns, disease outbreaks or extreme weather. Our 2021 World Trade Report showed that greater trade diversification in 2008 was correlated with lower GDP growth volatility over the subsequent decade. This relationship will become increasingly salient as climate-related shocks become more widespread.

Note: The diversification index is based on the Herfindahl-Hirschman index of geographical export concentration and ranges from zero (no diversification) to one (complete diversification). Volatility is computed as the standard deviation of the ten yearly GDP growth rates.

Turning now to the past three years, an underappreciated fact is that trade has been an important shock absorber.

At the macro level, global goods trade rebounded strongly from the lockdowns and was setting new records by early 2021, helping drive economic recovery. Last year, global goods and services trade was 7% higher in real terms than its pre-pandemic peak.

During the pandemic, trade and multi-country supply chains quickly became vital mechanisms for ramping up the production and distribution of medical supplies. Billions of COVID-19 vaccine doses were manufactured in supply chains cutting across as many as 19 countries. The volume of food traded around the world held steady. Absent trade, COVID-19 would have been harder, not easier, to cope with.

Over the past year and a half, deep and diversified global markets have helped countries mitigate disruptions arising from the war in Ukraine: for instance, Ethiopia sourced wheat from the United States and Argentina after its imports from the Black Sea region were cut off. Europe could make up the loss of piped Russian gas by importing liquefied natural gas from elsewhere.

A retreat from open global trade would undermine this supply “flexicurity” that comes when firms and households have more outside options from which to purchase goods and services. It would contribute to increasing price pressures and macro volatility, and make it harder to scale up and diffuse the green technologies we need to get to net zero emissions. Furthermore, fragmentation would be very costly: WTO economists estimate that if the world economy decouples into two self-contained trading blocs, it would lower the long-run level of real global GDP by at least 5%, with some developing economies facing double-digit welfare losses.

Meanwhile, the data increasingly shows that the recent supply chain problems were rooted in the pandemic. Locked-down consumers pivoted massively from services to more heavily traded goods. Producers and ports, often constrained by pandemic restrictions, struggled to keep up. But supply chain pressures are now back to or even below pre-pandemic levels, as illustrated by the New York Fed’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index. Current clouds on the trade horizon have more to do with insufficient demand than too much of it. Eurozone output has been flat, and recent data for China in particular point to slowing growth, declining exports and imports, and falling producer and possibly consumer prices.

But it would be wrong to conclude from all this that nothing needs to change in the way global trade operates. The past three years exposed genuine vulnerabilities in a handful of products and trading relationships where excessive concentration prevents the kind of supply flexicurity I was just describing. Re-globalization would tackle these concentration problems by bringing more countries and communities into deeper, more diversified international production networks. It would also make commercial relationships harder for any single country to weaponize.

My remaining remarks will look at how re-globalization and trade can continue to drive growth, development and price stability.

One intriguing new finding by WTO economists is that despite all the tensions and scepticism around trade, overall trade costs for agricultural products, manufactured goods, and services have fallen by 12% over the past twenty years.

In other words, despite some higher policy costs like tit-for-tat tariffs among major trading nations and rising non-tariff barriers, trading goods and services across borders has in aggregate become cheaper, once we account for improvements in transport, communications, regulatory, transaction, and information-related costs, alongside governance factors. This is significant because trade cost reductions have historically been a major driver of trade growth.

Between 1996 and 2018, trade costs fell by more than a quarter in countries like Vietnam, Poland, and India. There is still room to improve: trade costs in developing economies remain almost 30% higher than in high-income economies — and are 50% higher in Africa.

Trade policy and the WTO have played an important role in these reductions. The WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement lowered non-tariff trade costs by simplifying and harmonizing rules around border procedures. Average tariffs have fallen to about half their level in 1995 through unilateral reforms as well as WTO accession, plurilateral arrangements like the WTO’s agreement on high tech goods, and regional agreements.

Another potential driver for trade and re-globalization is services, which are becoming increasingly tradeable.

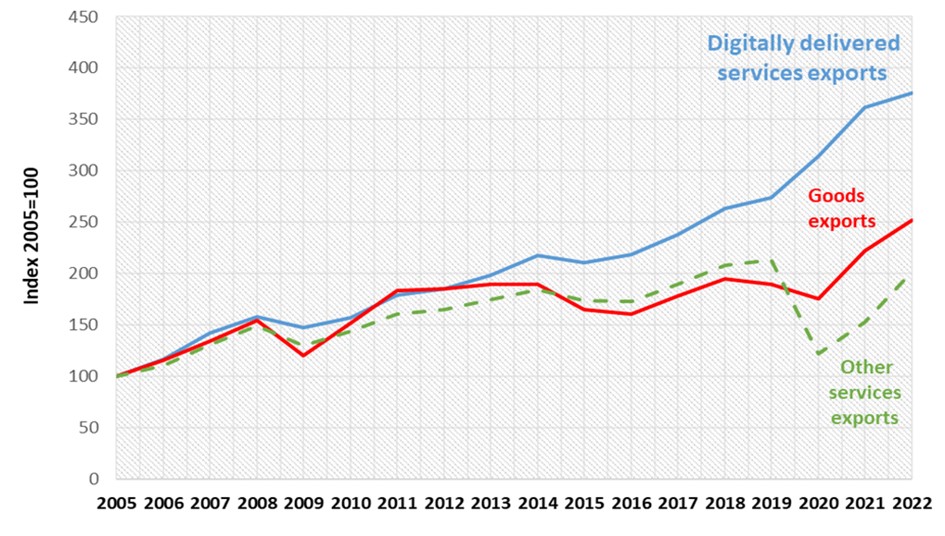

Global exports of services delivered via computer networks — things like streaming entertainment, remote learning, software services and cloud computing — have more than tripled since 2005, growing far faster than exports of goods and other services. At $3.82 trillion in value, digitally delivered services accounted for 12% of total global trade in 2022, compared to only 8% a decade before. They also emerged as increasingly important inputs into the production of other services.

In fact, Richard Baldwin at the Graduate Institute in Geneva predicts that services is due for an “unbundling” analogous to what we saw with goods a generation ago. This time, it will be white-collar offices instead of factories that stretch across borders, as services firms in rich countries offshore intermediate tasks to lower wage countries and use remote-work tools to ensure coordination and quality.

Increased digitalization and trade in services could become a powerful disinflationary force, with implications for monetary policy — and for social policy.

Too many governments dropped the ball on supporting dislocated workers during the goods supply chain boom. We cannot afford to repeat that mistake with services, whether it’s about trade or the widescale adoption of AI.

At the WTO, we have an ongoing agenda to reduce services-related trade costs. About 70 of our members, together accounting for over 90% of global services trade, have signed on to an agreement on Services Domestic Regulation that cuts red tape, sets out best practices, and make rules more transparent. And a group of 90 members including the US, the EU and China, are currently negotiating a set of basic global rules for digital trade.

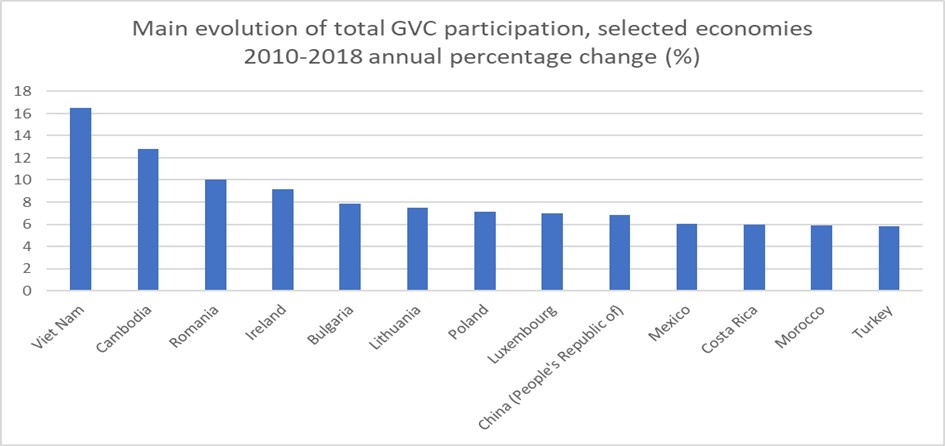

Some evidence of re-globalization was visible even before the recent crises, with countries like Vietnam, Cambodia, Romania, Morocco, and Turkey sharply increasing their participation in value chains across a range of goods and services.

Source: WTO calculations based on the OECD TiVA database

WTO analysis suggests that China’s position in bottleneck products, defined as heavily traded goods with few suppliers, has declined by 8.5 percentage points from its 2015 peak of 40%. However, the share of bottleneck products in total global trade remains high, at around 20%.

Today, as businesses recalibrate how they think about scale efficiencies versus concentration risks, they have an opportunity to bolster supply chain resilience by taking this diversification process further, to encompass more places in Africa, Asia and Latin America that have good macroeconomic fundamentals but remain stuck on the margins of the global division of labour. These regions offer younger workforces and reserves of potential productivity increases. A more deconcentrated, shock-resistant global supply base would help return trade to its familiar role as a force for price moderation.

In sum, there is a strong case for diverting some of the energy behind reshoring to re-globalizing production instead.

Re-globalization requires a supportive trade policy environment, including action at the WTO and elsewhere to keep lowering trade costs, narrowing the digital divide, and making trade finance more available.

Let me now conclude. The traditional objective of the trade policy community has been predictability. This focus has served the central banking community’s goal of price stability.

A world that turns its back on open and predictable trade will be one marked by diminished competitive pressures and greater price volatility. It would be a world of weaker growth and development prospects, a slower low-carbon transition, and increased supply vulnerability in the face of unexpected shocks.

Re-globalization is a far better alternative. I ask all of you to speak up for open trade, multilateral cooperation, and the WTO. Doing so might even end up making your jobs a bit easier.

Thank you.

Share

Reach us to explore global export and import deals