In today’s world, policymakers have divergent views on many trade issues. But when it comes to making commerce more inclusive, from Barbados to Cambodia, from Colombia to Kenya, from Pakistan to the United States and more, the goal of bringing more people to participate in cross-border exchanges of goods and services is broadly shared. The reason is clear: trade offers a path to prosperity. Policymakers know it, and so do individuals and businesses, which is why they want to explore foreign markets, make new connections, and engage in regional and global commerce.

While there is general consensus on the aim of broadening participation in international trade, different perceptions abound concerning which policies can help achieve this objective. Even as the evidence shows that the gains from trade are significant, the misguided idea that one country’s gain is another country’s loss can sometimes cloud policymaking.

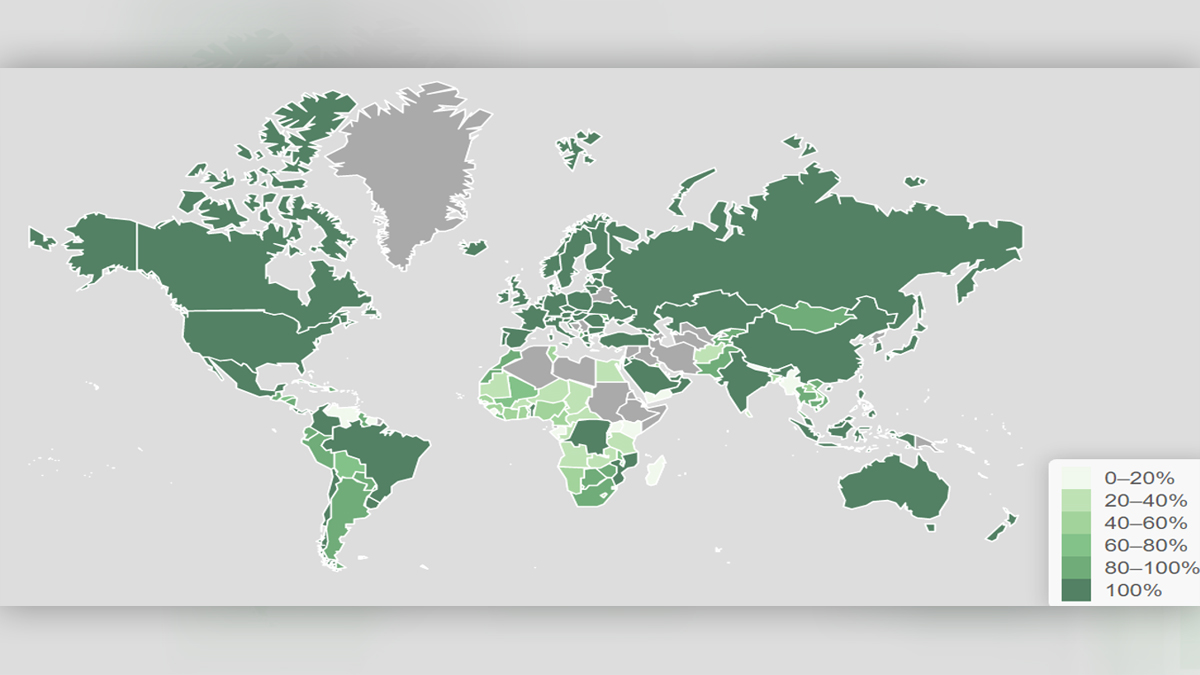

One prescription, however, is bulletproof: trade must be faster, easier and less costly. The World Trade Organization (WTO), through its rules, experience-sharing and capacity-building efforts, can help governments to ease trade and unleash private sector cooperation. By bringing a renewed focus on effective implementation of the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) (see Figure 1) as well as on leveraging advanced technologies and on using expedited trade measures to support the green transition, more people can be empowered to trade.

Figure 1: Progress on TFA implementation commitments

Source: WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement Database (accessed 26 April 2023).

Trade can benefit the many

The role of trade in driving unprecedented poverty reduction over the past 40 years has been well documented. But the COVID-19 pandemic has caused efforts to eradicate poverty and reduce inequality to be severely hampered. The situation has been further exacerbated by high inflation and the war in Ukraine. More and more inclusive trade is needed.

Exports can open new job opportunities, raise incomes and bring about an increase in skills. A report from the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Bank shows that increasing exports per worker results in higher wages and lower levels of informal work for many marginalized groups. Another study finds that exporting firms employ more women than non-exporting firms. In addition, this study highlights that women employed in sectors with high levels of exports are more likely to be formally employed in jobs with better benefits, and trade increases both women’s wages and economic equality.

A forthcoming publication from the WTO and the World Bank will confirm that the growth of services trade has translated into an increasing number of jobs linked to services exports, including in developing economies, and that smaller firms play a key role.

Imports of both goods and services are also important. They apply downward pressure on prices and expand consumer choice. They also help to improve living standards, particularly for the poorest households in both advanced and developing countries, which spend a relatively large share of their income on heavily traded goods such as food and clothing. In addition, imports of high-quality, competitively priced intermediate inputs can boost the productivity of domestic firms.

The gains from trade are not automatic, however. Complementary policies and institutions are key to unleash them. In a similar vein, appropriate policies are needed to manage risks to the most vulnerable and to smooth adjustment costs of trade shocks.

But obstacles can limit participation in trade

International trade is not just a powerful driver of economic growth, but also a complex system of cross-border business transactions. It involves a multitude of participants, both public and private, and it is heavily dependent on documents, processes, procedures and infrastructure, all of which are essential to move things from one place to another.

While no good purpose is served by making it more difficult and expensive to engage in commerce, obstacles – such as inefficient customs and border management practices and regulations, outdated trade and transport-related infrastructure, or inefficient and expensive shipping and logistics services – very often get in the way of efficient trade. Other factors can also impact whether people can benefit from trade, including, for example, low access to trade finance or a limited capacity to comply with standards.

The recent World Bank Logistics Performance Index (LPI) presents the latest views on the network of services that support the physical movement of goods across 139 countries. The LPI shows that, while overall performance has improved, compared with previous years, there is still much to be done. For example, according to the LPI, the average time required, across all potential trade routes, for a container ship to move from port of export to port of destination is 44 days, with a standard deviation of 10.5 days. For most of this time, the ship is at sea, but it undergoes significant delays at the ports of origin and destination – delays which could be reduced or avoided. Interestingly, although the top performers in the index are advanced economies, performance transcends income levels.

The WTO is an instrument to facilitate trade for inclusion

Burdensome customs procedures, as well as other factors that increase the time and cost to import and export, disproportionately affect those with the least resources to deal with them – in particular small businesses and the poorest countries. Tools that reduce trade costs can be a game-changer.

Several WTO agreements help to lower trade costs, the principal one among them being the TFA, which came into effect in 2017.The TFA provides a framework for expediting the movement, release and clearance of goods, including goods in transit, while establishing measures for effective cooperation between customs and other authorities on trade facilitation and customs compliance issues. It contains provisions on the key tools that modern customs services rely on to perform their functions, including risk management, single windows, and measures for authorized operators, among others.

As a multilateral agreement, the TFA is valuable largely because it serves as both an anchor and a catalyst of domestic efforts to engage in trade facilitation. The TFA requires all trading partners to invest in trade facilitation. It prevents governments from backtracking in the face of anti-facilitation lobbies. It fosters the adoption of common procedures and requirements, eliminating documentary redundancy. In addition, it mobilizes donor support to help build capacity in developing countries.

In one of the first efforts to empirically assess the post-implementation impact of the TFA, a recent WTO study shows that the TFA has led to a US$ 231 billion increase in trade, with an average 5 per cent increase in global agricultural trade, a 1.5 per cent increase in manufacturing trade and a roughly 1 per cent increase in total trade. The analysis confirms the TFA’s pro-development dividend: least-developed countries have benefited the most, with their agricultural exports increasing by 17 per cent, their manufacturing exports by 3.1 per cent and their total exports by 2.4 per cent. The estimates further point to an increase in agricultural trade of between 16 and 22 per cent among developing members that have made TFA commitments.

Effective, digitized and green trade facilitation measures can bring more people to trade

Looking ahead, doubling down on trade facilitation will be critically important to broaden the participation of many more people in trade. According to the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement Database, about a quarter of the measures in the TFA still remain to be implemented, with the largest gains to be achieved in the developing world (see Figure 1). Technical assistance and capacity-building to support implementation are readily available.

In terms of what is happening on the ground, there is room to make trade facilitation measures work better in practice. In a recent presentation to the TFA Committee, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) highlighted that improving operational practices, including those related to border automation and streamlining border procedures, could yield big payoffs.

The ability to harness new technologies has become a key means to drive trade facilitation, and digital technologies are already influencing the way customs work. A recent survey conducted by the World Customs Organization (WCO) and the WTO showed that, out of several so-called disruptive technologies, data analytics and artificial intelligence (AI) were having the biggest impact on customs operations. These new technologies are already being used for data mining for intelligence purposes and risk management, as well as for post-clearance audits and controls, for developing AI-based models for interpreting X-ray images, and more. Exchanges of experiences among national border agencies on the use of digital technologies can help countries learn from each other’s successes and avoid costly mistakes.

As the world faces more frequent and intense climate change-related incidents, trade facilitation, as part of a broad-based trade and climate adaptation strategy, will play an increasing role in strengthening economic resilience. Trade facilitation can help to do this by lessening the impact of climate-induced increases in trade costs and by strengthening food security during climate-induced supply-side disruptions. It can also support preparedness, recovery and rehabilitation from climate disasters. Looking more broadly at the transition to a sustainable future, trade facilitation will also be key to support efforts by businesses to turn their linear supply chains into circular that help use resources more efficiently and reduce waste

Recent crises have taken a toll on economic activity, which is projected to fall from 3.4 per cent in 2022 to 2.8 per cent in 2023. But concerns run deeper. With global potential growth falling to an average of 2.2 per cent a year between 2022 and 2030 – the lowest growth rate in 30 years – the World Bank fears that a lost decade is in the making. Countries’ ability to tackle debt crises, combat poverty and social exclusion, and fight climate change could be significantly curtailed. Removing the impediments that raise trade costs could help reinvigorate world trade.

There is no question that trade facilitation measures, backed by strong support for their implementation in the poorest countries, are a central component of an ambitious global partnership to get global growth back on track.

Reach us to explore global export and import deals